A contemporary series on the endovascular management of visceral aneurysms and pseudoaneurysm

| Available Online: | January, 2024 |

| Page: | 3-7 |

Author for correspondence:

Ahmed Elshiekh

Birmingham Vascular Center, University Hospitals Birmingham

E-mail: dr.ahmed.elshiekh1@gmail.com

doi: 10.59037/qt960q86

ISSN 2732-7175 / 2024 Hellenic Society of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery Published by Rotonda Publications All rights reserved. https://www.heljves.com

Abstract

Full Text

References

Images

Abstract

Introduction: Visceral artery aneurysms (VAAs) and pseudoaneurysms are uncommon. Endovascular management is now the treatment of choice with either exclusion or occlusion. We report on our experience in a tertiary referral centre of elective and emergency VAAs and pseudoaneurysm treatment.

Patients and methods: A retrospective review of all VAAs and pseudoaneurysms cases treated using endovascular means over 8 years period. Follow up included clinic reviews as well as data on the system from admissions to other specialities including emergency department presentations.

Results: 53 visceral aneurysms in 50 patients were treated with endovascular techniques. 29 (58%) of the patients were males. The mean age was 62 years (range: 20-88). 26 (49%) were true aneurysm. 40% presented with rupture at the time of diagnosis. Technical success was achieved in 48 of the patients (96%). 78% of the cases had occlusion treatments coils or glue. The mean follow-up period was 3.3 years (range: 1 month to 10 years). The 30 days mortality was 8%. Two patients (4%) had clinical symptoms secondary to organ mal-perfusion. Five patients (10%) required subsequent re-intervention.

Conclusion: VAA and pseudo aneurysms can be treated successfully with endovascular means both in the elective and emergency settings. In our experience, the majority of patients are suitable for occlusion therapy without any risks of clinically significant organ ischemia.

Key words: Visceral aneurysm, Visceral pseudo aneurysm, Endovascular surgery, Mesenteric aneurysm

Full Text

INTRODUCTION

Visceral artery aneurysms (VAAs) and pseudoaneurysms are uncommon with an incidence rate of 0.01% to 0.2%1. However, their detection rates are increasing due to the widespread advancement and availability of cross sectional imaging. The VAAs and pseudoaneurysms occur mainly in the splenic and hepatic vessels but are also recognised in renal, gastroepiploic, pancreaticoduodenal, gastroduodenal, celiac, superior mesenteric, or inferior mesenteric arteries. The vast majority of the cases are incidentally found and are essentially asymptomatic whilst few cases present with symptoms of rupture.

Pseudoaneurysms are treated irrespective of their size due to the high risk of rupture and bleeding while true aneurysms are treated once they reach the size threshold or if they become symptomatic2, 3.

Over the last decade the endovascular management of these pathologies has gained popularity given the reduced mortality, complications rate, and hospital stay in comparison to the open procedures4. The endovascular treatment techniques involves either exclusion or occlusion of the pathological segment which can be achieved by using stent grafts, coils, vascular plugs, occlusion devices or liquid embolics5 when size exceeds 5cm visceral aneurysms are considered as “giant” (giant visceral artery aneurysms or GVAAs4, 6, 7.

We report on our experience in a tertiary referral centre management of elective and emergency VAAs and pseudoaneurysms.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A retrospective review of all VAAs and pseudoaneurysms cases presented to our unit from the year 2008 till 2015 were identified from hospital electronic records. Cases after 2015 were not included to allow a long follow up period and the subsequent covid pandemic. Both elective and emergency cases were included. Only cases treated endovascularly were included. Preoperative diagnosis was based on imaging mainly by computed tomography scans. There was no uniform protocol for post operative imaging as this was variable depending on the physician in charge.

Follow up included clinic reviews as well as data on the system from admissions to other specialities including emergency department presentations and scans done for other reasons.

The statistical analysis was performed in R environment (R version 4.0.3, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; https://www.r-project.org) using pre-specified data analysis plan. Data characteristics were assessed using dplyr package and data missingness was assessed using naniar package. Missing data were treated by pairwise deletion. Continuous variables were presented as median [interquartile range; IQR] unless stipulated otherwise; categorical data were presented as frequencies (%) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) if required. Student’s t-test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test were used to compare continuous data. Pearson’s chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test with continuity correction were used to analyse categorical data. Logistic regression was used to calculate the dichotomous data.

The project was approved by the hospital audit department. A formal ethics approval was not required as the project only included retrospective data collection.

RESULTS

53 visceral aneurysms were treated by endovascular techniques in 50 patients during the study period. 29 (58%) of the patients were males. The mean age was 62 years (range: 20-88). Three of the patients had connective tissue disorder, one with Marfan syndrome and two with Poly-Arteritis Nodosa (PAN). 26 (49%) of the identified cases were true aneurysm. 50% of the patients were asymptomatic, 10% symptomatic but not ruptured while 40% presented with rupture at the time of diagnosis.

61% of symptomatic cases presenting with rupture and bleeding were attributed to pseudoaneurysms. Among the true aneurysms presenting with rupture, three were hepatic with sizes measuring 37mm, 16mm, and 25mm, one splenic aneurysm measuring 33mm and one coeliac aneurysm measuring 24mm.

The mean sac size was 30.8 mm (range: 12-112). Common vessels affected with VAA and pseudoaneurysms were in the hepatic artery (70%), splenic (23%), coeliac, superior mesenteric and two cases in the gastroduodenal and transplant renal arteries (1.8% in each). The aetiology of these VAA/VAPA were variable including postoperative (28%), degenerative (28%), traumatic (20%), inflammatory causes (18%) as well as other causes (6%) including congenital causes, malignancy and post procedures like liver biopsy or Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS).

Technical success was achieved in 48 of the patients (96%). The single case in which technical success was not achieved presented with bleeding post liver biopsy and was haemodynamically unstable at presentation. Unfortunately, this patient suffered a cardiac arrest before the attainment of endovascular access and successful sealing could be accomplished. 78% of the cases had occlusion treatments in the form of coils or glue. 22% had exclusion treatment with stent grafts with or without coils. The figure below (figure 1) shows pre operative CT scans and post operative angiography of treated aneurysms.

A significant proportion of cases requiring open surgical intervention were iatrogenic in nature, stemming from complications secondary to recent surgical procedures such as hepatic surgery. These cases often necessitate re-exploration in a surgical setting, by the initial operating team with help from the vascular surgeons.

The mean follow-up period was 3.3 years (range: 1 month to 10 years). The 30 days mortality was 8% as four patients died during this period all of which presented with acute postoperative or post intervention bleeding that has initially lead to the pseudoaneurysm or aneurysmal bleeding (3 post-abdominal surgery, one post liver biopsy). Technical success with control of bleeding was achieved in three of these four patients with failure to stop the bleeding in the fourth patient. One patient died of post-operative sepsis; another patient died secondary to cardiac arrhythmias. The cause of death was not recorded in the last patient.

During the post operative 30 days period 7 patients (14%) had radiologic signs of organ ischaemia with no clinical consequences ( 6 in the spleen and one in the liver ). Of those seven patients, 6 had occlusion therapy and one had an exclusion procedure. Two patients (4%) had clinical symptoms secondary to organ mal-perfusion as one patient developed an abscess that required radiologic drainage and the other patient suffered loss of the transplant kidney. These two patients had exclusion procedures.

The three cases of connective tissue diseases manifested as symptomatic emergency cases, with two cases presenting with rupture and the third case exhibiting a mycotic aneurysm who was deemed unsuitable for open surgery due to the prior occurrence of heart valve replacement and concurrent full anticoagulation at the time of presentation. Despite these complexities, all three cases achieved technical success, leading to subsequent discharge. Follow-up assessments revealed favourable outcomes with survival till the end of follow up in two cases. The third case died three years later due to unrelated cause.

Five patients (10%) required subsequent re-intervention which were all endovascular reinterventions (coil/ glue/ re-stent). During the subsequent follow up period 8 patients died. The causes of death were identified in three of these cases and were unrelated to the intervention (pneumonia in two cases and decompensated liver disease in one case). The cause of death was not available in the rest of these cases.

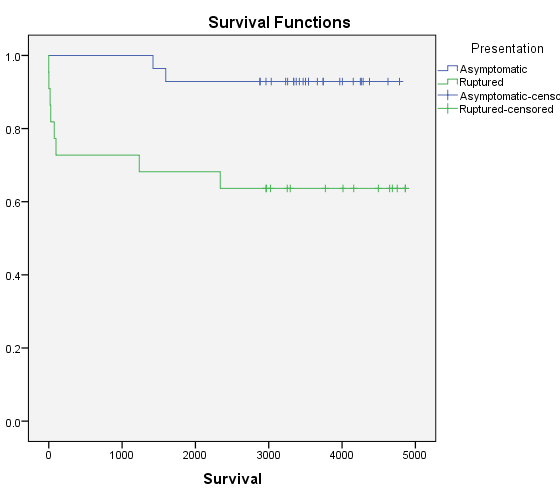

There was an association between the acute presentation with rupture and post-operative mortality (20%, P< 0.013). This is highlighted in the Kaplan Mayer curve for survival shown in figure 2.

There was also an association between aneurysm size and developing end organ ischemia (Odds Ratio: 1.10, 95%C.I.: 1.03-1.17, P <0.004918).

DISCUSSION

The risk of rupture of visceral pseudoaneurysms is up to 76.3 % irrespective of the size whilst the risks of VAA rupture is less than that of the pseudoaneurysms but remains high at about 25-40% once it is greater than 25mm in diameter. Hepatic artery aneurysms are more susceptible to rupture (up to 80%) followed by pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysms with rupture rates up to 75%8, 9. Thus, the treatment of these cases in the asymptomatic phase before rupture is recommended by the European and American guidelines2, 10. The European guidelines advice repair in asymptomatic true aneurysms if the size is above 25mm and consideration of intervention at any size for pancreaticoduodenal and gastroduodenal arcades as well as of the intra-parenchymatous hepatic arteries. The American guidelines recommend a size threshold of 20 mm for the hepatic and coeliac true arteries and a 30 mm threshold for the splenic artery true aneurysms. Pseudoaneurysm should be treated at any size due to the high risk of rupture.

In our series, we had 53 aneurysms in 50 patients. Previously published data have reported between 41 to 45 treated cases per series with follow up to ten years. We had a mean follow up of three years which was similar to the mean follow up in other published series6, 9. 40% of cases in our series presented with rupture which was similar to that of 46% reported in literature6. In our series VAA and pseudoaneurysms were most commonly found in the hepatic, splenic arteries with minimal numbers in the renal arteries. In contrast other studies found highest incidence in the splenic artery followed by the coeliac trunk, the renal and hepatic arteries9. A systematic review found the highest number of reported cases to be in the renal artery followed by the splenic then the hepatic arteries11.

In our series, all the post interventions deaths occurred in patients who presented with symptoms of rupture with no mortality in patients who were asymptomatic. We also found that presentation with rupture carries a statistically significant risk of post intervention mortality (20%, P< 0.013). This is similar to the reported high mortality rates in the cases presenting with ruptures in the literature which is around 25%12 but when they present as a rupture, a high mortality is associated. Material and Methods: We review our experience of 18 cases between 1988 and 2006. Results: 9 males and 9 females with a mean age of 66,5 years are analyzed. Aneurysms were located in splenic artery9, 8. Other cases series reported no mortality in asymptomatic cases treated with endovascular modalities which was the same as our experience9. This may be explained by the fact that these patients are often unstable with deranged physiology as a result of the initial shock cause by the acute bleeding. We also found that increase in sac size is associated with development of end organ ischemia with intervention.

Technical success in our series was high at 96% which was similar to that reported in literature6. The feasibility of the use of stent grafts for excluding visceral aneurysms/pseudoaneurysms is dependent on the arterial anatomy, location of , sac size and the ability to navigate the stent graft into the target vessel. It is also more technically demanding than occlusion therapy. Our data has demonstrated that occlusion therapy is safe with no risks of clinically significant organ ischaemia happening as a consequence of the occlusion. Interestingly the two cases in our series that had clinical consequences of organ malperfusion were treated with exclusion rather than occlusion therapy. An association was found between the aneurysm size and the risk of developing end organ ischemia (odd ratio 1.10 C.I. 1.03-1.17 P <0.004918). An association between the aneurysm size and the risk of developing end organ ischaemia has not been demonstrated in other series although an association with preoperative splenomegaly as well as the more distal aneurysm site has been suggested13.

We had an acceptable reintervention rate of ten percent in our endovascular series. In a large systematic review, the reintervention rate following endovascular repair of the splenic artery aneurysms was 7% and was much higher at 40% for the hepatic artery11. The systematic review also showed much lower reintervention rates after open repair as expected.

Some of the limitations of this study include that fact that is a retrospective review and the lack of uniformity of the post-operative imaging or follow up protocols. Furthermore, our study did not delve into a detailed analysis of the open cases or the criteria guiding the decision-making process regarding the choice between open and endovascular treatment approaches. However, the data presented demonstrates the safety and efficacy of occlusion techniques for endovascular management of VAAs and pseudoaneurysms in the majority of patients. We have also not looked at patients undergoing open interventions.

CONCLUSION

Visceral artery aneurysms and pseudo aneurysms can be treated successfully with endovascular means both in the elective and emergency settings. In our experience, the majority of patients are suitable for occlusion therapy without any risks of clinically significant organ ischemia.

References

- Røkke O, Søndenaa K, Amundsen S, Bjerke-Larssen T, Jensen D. The diagnosis and management of splanchnic artery aneurysms. Scand J Gastroenterol [Internet]. 1996 [cited 2023 Mar 11];31(8):737-43. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8858739/

- Björck M, Koelemay M, Acosta S, Bastos Goncalves F, Kölbel T, Kolkman JJ, et al. Editor’s Choice e Management of the Diseases of Mesenteric Arteries and Veins Clinical Practice Guidelines of the European Society of Vascular Surgery (ESVS). 2017 [cited 2023 Mar 18]; Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2017.01.010

- SVS Management of Visceral Aneurysms Guideline Summary [Internet]. [cited 2023 Mar 18]. Available from: https://www.guidelinecentral.com/guideline/41128/

- Balderi A, Antonietti A, Ferro L, Peano E, Pedrazzini F, Fonio P, et al. Endovascular treatment of visceral artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms: our experience. Radiol Med [Internet]. 2012 Aug [cited 2023 Mar 11];117(5):815-30. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22228131/

- Tipaldi MA, Krokidis M, Orgera G, Pignatelli M, Ronconi E, Laurino F, et al. Endovascular management of giant visceral artery aneurysms. Sci Reports 2021 111 [Internet]. 2021 Jan 12 [cited 2023 Mar 11];11(1):1-6. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-80150-2

- Cappucci M, Zarco F, Orgera G, López-Rueda A, Moreno J, Laurino F, et al. Endovascular Treatment of Visceral Artery Aneurysms and Pseudoaneurysms With Stent-Graft: Analysis of Immediate and Long-Term Results. Cirugía Española (English Ed [Internet]. 2017 May 1 [cited 2023 Mar 11];95(5):283-92. Available from: https://www.elsevier.es/en-revista-cirugia-espanola-english-edition–436-articulo-endovascular-treatment-visceral-artery-aneurysms-S2173507717301047

- Obara H, Kentaro M, Inoue M, Kitagawa Y. Current management strategies for visceral artery aneurysms: an overview. Surg Today [Internet]. 2020 Jan 1 [cited 2023 Mar 11];50(1):38-49. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00595-019-01898-3

- Juntermanns B, Bernheim J, Karaindros K, Walensi M, Hoffmann JN. Visceral artery aneurysms. Gefasschirurgie Zeitschrift fur vaskulare und endovaskulare Chir Organ der Dtsch und der Osterr Gesellschaft fur Gefasschirurgie unter Mitarbeit der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft fur Gefasschirurgie [Internet]. 2018 Jun 20 [cited 2018 Jun 30];23(Suppl 1):19-22. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00772-018-0384-x

- Pitton MB, Dappa E, Jungmann F, Kloeckner R, Schotten S, Wirth GM, et al. Visceral artery aneurysms: Incidence, management, and outcome analysis in a tertiary care center over one decade. Eur Radiol [Internet]. 2015 Jul 8 [cited 2023 Mar 13];25(7):2004. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC4457909/

- Chaer RA, Abularrage CJ, Coleman DM, Eslami MH, Kashyap VS, Rockman C, et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery clinical practice guidelines on the management of visceral aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2020 Jul 1;72(1):3S-39S.

- Barrionuevo P, Malas MB, Nejim B, Haddad A, Morrow A, Ponce O, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the management of visceral artery aneurysms. J Vasc Surg [Internet]. 2019 Nov 1 [cited 2023 Mar 15];70(5):1694-9. Available from: http://www.jvascsurg.org/article/S0741521419303611/fulltext

- Ruiz-Tovar J, Martínez-Molina E, Morales V, Sanjuanbenito A, Lobo E. Evolution of the therapeutic approach of visceral artery aneurysms. Scand J Surg [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2023 Mar 13];96(4):308-13. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18265859/

- Sachdev U, Baril DT, Ellozy SH, Lookstein RA, Silverberg D, Jacobs TS, et al. Management of aneurysms involving branches of the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries: A comparison of surgical and endovascular therapy. J Vasc Surg. 2006 Oct 1;44(4):718-24.

- Saltzberg SS, Maldonado TS, Lamparello PJ, Cayne NS, Nalbandian MM, Rosen RJ, et al. Is endovascular therapy the preferred treatment for all visceral artery aneurysms? Ann Vasc Surg [Internet]. 2005 [cited 2023 May 24];19(4):507-15. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15986089/